For years I felt like a ghost. That is, spectral, with a vitamin D deficient translucence, a player of haunting visions. Lately I find the spirit image too immaterial and atemporal for what a projectionist is. The projectionist is above all analog, an operator, more suitable to the cinematic trope of undercover agent. The undercover agent is an unseen person, a profoundly pre-digital body, linked to the filmic by formula, corporeality, and analog means. To be an undercover agent is to be constantly, objectively attentive. Like the agent, the projectionist is trained to detach emotionally in service of the job at hand.

The following details a brief, general overview of a quotidian experience projecting 35mm reel-to-reel film. It is not comprehensive. Each film projection environment has countless individual variables: projector model, film gauge, film condition, venue and event context, program type, etc. This is a shorthand, personal, “learned in the field” summary to identify the role of the operator and describe a few mechanics of running successful film screenings.

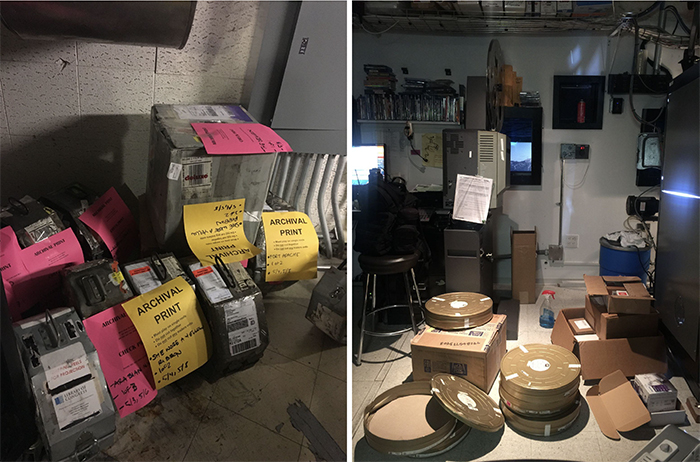

It’s an average 12-hour day. You might be surrounded by film prints. The materiality of film, its literal weight, is striking. A print typically arrives in protective, hexagonal cans or a cardboard box, on shipping reels or wound tightly on plastic cores. If a core is broken, or missing, an emergency make-shift core can be figured from cardboard. Don’t trust labels: film packaging and prints can have shady pasts. Verify that what has been delivered is the correct film, sometimes even the correct version of a film. Confirm that the shipment contains all reels and estimate whether their length approximates the published running time of the film. Document and note if the print has been shipped in a way that compromises its condition. When shipped, a print should always be secured with at least 6 inches of acid-free artists tape.

While the booth is calm, start on print inspections. The inspection, upon a rewind bench with a light box, is the vital preparatory step to ensure the most flawless and beautiful possible presentation. The projectionist gathers every bit of information which is recorded in the “Inspection Report.” A physical print contains clues in both its tactile materiality and its printed image. Your first encounter with the leader, head or tail, already elucidates a film’s past and present. The ends of the reels, most exposed, absorb the most abuse. Check the countdown and changeover cues of each reel for accuracy even when the leaders are uncut; more often than not these will need to be modified or qualified. A frame counter (acquire one which counts frames as well as feet) is necessary. Measure and mark the appropriate start frame using artists tape. Never use masking tape. Masking tape does not belong in a projection booth. The standard placement for a head cue is 8 feet from the first image but can vary based on projector motor pick-up; in this particular booth, with these particular projectors, I mark 7 feet. Standard motor cues measure at 10 ft 12 frames and the changeover cue at 18 frames from the last image. (The distance between the motor and changeover cues is approximately 8 revolutions of a 2k foot reel.) Ideally the projectionist will not need to add new changeover cues at the tail of the reel. If the cues are off by some frames, note this on the Inspection Report and the operator can instinctively adjust the changeover timing. If cue marks must be added, whether missing, radically inaccurate, or multiple sets, add cues using only a grease pencil slash. Never touch the picture space! Check end splices for resilience and framing accuracy; if necessary, use fingernails — not a blade — to peel old tape, and repair with a splicer and clear splicing tape.

On the bench, the projectionist analyzes the image, identifying the intended aspect ratio and sound format. Note the film’s first and final image/credit, whether the film opens or ends with sound fade-in or out. This information is gathered by looking at the physical frames of the print, and at times by applying historical knowledge of formats and context: a commercial film likely adheres to historical conventions, art films have promiscuous proclivities.

In inspection, the projectionist preps the print for optimal presentation by assessing the physical condition of the film. Pristine or damaged, these beautiful material objects have lived experience inscribed upon their surfaces. Inspect the length of every reel by running your fingers only along the edges. Cotton gloves can catch torn perfs and exacerbate damage, or may dull one’s touch and neglect splices altogether. An experienced projectionist can identify and repair most damage that might interfere with a smooth run through the machine, including broken perfs, torn frames, bad splices, sticky residue. Sticky residue can be removed with Goo Gone and a microfiber cloth. (Where I’ve worked, Goo Gone is archive-approved!) When necessary, do use cotton gloves to avoid touching the picture space of the film. Record all splices, base scratches (black) and emulsion scratched (green or white). Any shrinkage, warped or wrinkled film that may struggle in the projector should be flagged for special attention during screening. If a print smells of vinegar, it likely has other, sometimes imperceptible, physical issues.

Labeling the head leaders when existing labels are missing, confusing or incorrect, is done clearly and consistently using only artists tape. Film prints frequently leave the booth in better screenable condition than when they arrived.

It is noteworthy to remember that these are show prints; their entire purpose is to be screened. From an archivists perspective, every run through a projector is, in principle, damaging. The projectionist’s job is to regard and handle the film object with utmost care and attention to preserve its purpose — its screenable function. Film, never intended to be precious, now occupies an unusual role of being precious while subject to repeated use. The projectionist is a tender collaborator in this uncanny status.

Before each screening, clean the projectors. Remove and clean the gate with a penny and/or q-tip with alcohol. Toothbrush over the sprockets and wipe out any debris or dust. Blow with compressed air. Put the correct lens and plate in placement and project unimpeded light onto the screen. Here, check the screen masking and evenness of the projected light. Run the RP-40 test loop, adjust masking if necessary and focus both projectors. It is best practice to run the show print as little as possible to minimize exposure; however, it may be advised situationally to test a reel for questions arising during the inspection or at a programmer or filmmaker’s request.

The following happens over perhaps 40 seconds: Place the full reel, soundtrack side towards you, on the feed-out spindle and close the clamp. Pull the leader down to the empty take-up reel and wind a few times until the leader holds and framing guide reaches the gate. Make sure the take-up reel is clamped onto the spindle. Avoid bent reels, and never use tape to attach the film to any reel! Tape is a projector’s foil. Leader shouldn’t have to touch the floor; at the same time, the leader’s function is to front any unavoidable abuse. Set the intermittent by placing fingertips on the intermittent sprocket and rotating the wheel until the sprocket lands in its stasis position. Frame and secure the film in the gate. Thread the projector, then double check every loop, sprocket, and tension on the sound head. Setting the intermittent and threading becomes second nature and double checking compulsive. Motor the film down until the countdown marker sits in the gate, and listen! Irregular threading is something you hear. Check loops and sprockets one more time once the reel is in position. Over time, a projectionist’s relationship to a projector becomes instinctive; the sense of timing something experienced, not trained.

Waiting for the changeover cues is a peculiar kind of waiting. Your eyes, peering through a port window, abstractly fixate on the top right corner of the screen. Eyes blink one at a time. All action—on the screen or in the booth—falls away. When the first cue appears on screen, the projectionist starts the motor and opens the douser. A breath after the second cue, the protectionist presses a button or pedal and the image switches from projector to projector seamlessly.

Once the image hits the screen, pause and observe. Relieved waiting transforms into alert attentiveness to the screen. Listen to the projector and to the film traveling out and into the reels for any aberration. The projectionist sees the surface of the screen, not the action within. Check focus and framing spontaneously and diligently after every changeover. Once satisfied, retrieve the finished, flapping reel from the other projector. While rewinding that reel and threading up the next projector, an eye remains peripherally attuned to the screen. Unexpected annoyances — focal drift, frameline shifts — can appear while you are pursuing the routine tasks of rewinding, packing, and threading. To be a good projectionist is to be attentive to and resolve any issue before the spectator has a chance to notice, or remember.

A projectionist’s gaze is alert, objective and analytical. You do not see figures, characters, action, landscape or interiors, but line, grain, and edge. Your sight is only surface. You look at the tip of a nose as an edge, a wisp of hair as a shape, compare far left and right spaces. Sound can be confirmed through the booth monitor. Audio level and quality should be quickly checked at the beginning of the first reel with a swift and anonymous slip into the theater, if possible.

Any other presence in the booth is interference. This is an isolated existence. Enclosed in a room, the projectionist is removed from the cinematic illusion by layered glass, a hyper-alienation. At the same time, the projectionist alone engages with the screened film as pure object. Fingers learn to maneuver the material of film, deftly and gently, while the mind comprehends its fatal, immortal materiality. Film, durable and translucent, shiny and scarred, is inert, yet simmering with potential liveliness. Encountering the still frames in inspection, these otherwise unperceived or abstract moments act like 19th century spirit photography. Unseen except in static form, they become animated through the projector’s immaterial cast. In the unlit room, film projectors cast hot light in shadows, the booth is de facto noir. The projectionist/operator is part of an analog scene. When the screenings have ended, prints packed and projectors cool, you get outside into the late night finally, have a cigarette, maybe, like undercover agents do.